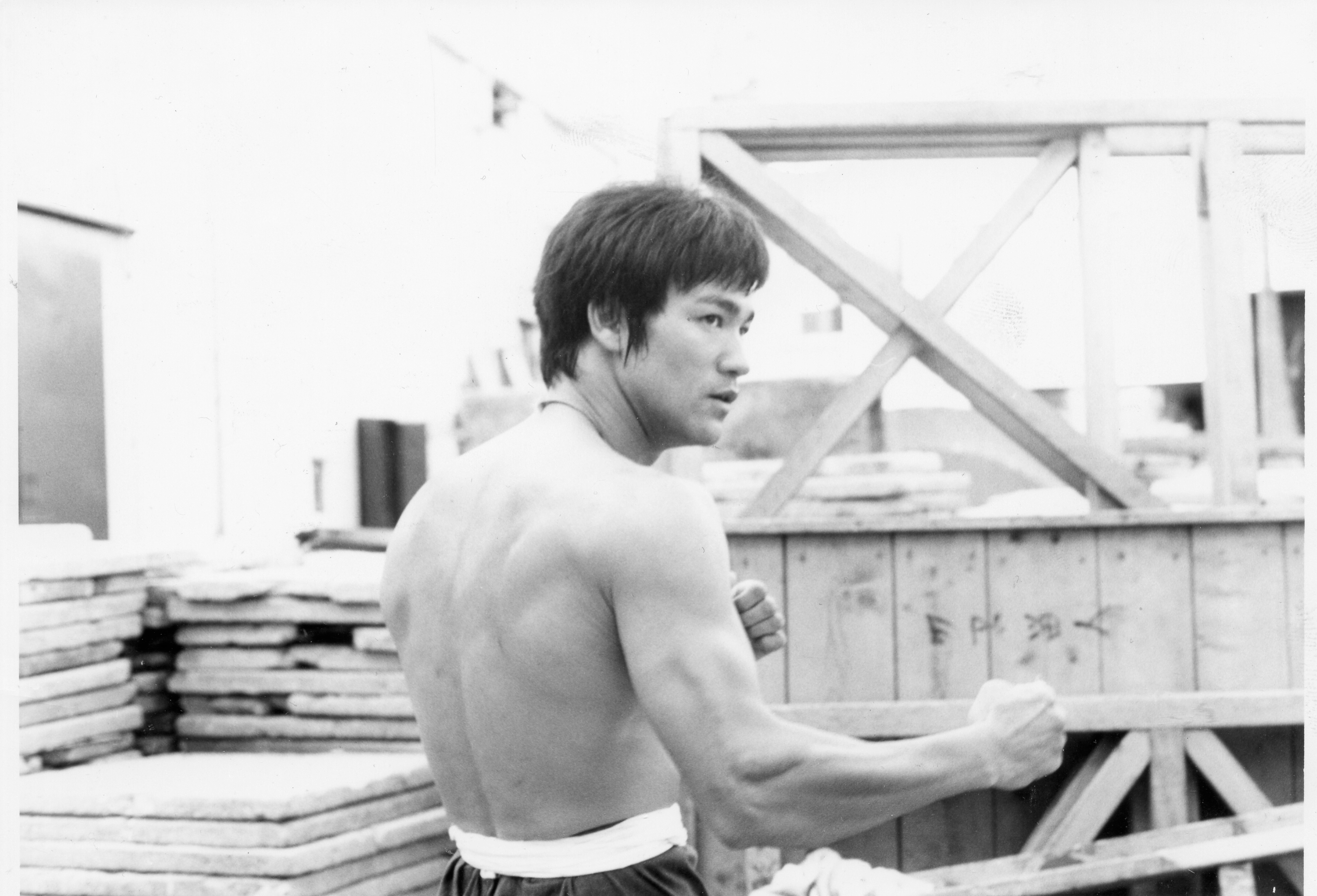

Bruce Lee will always be one of the most revered iconic action stars in cinema. In ESPN Films 30 for 30, Be Water doesn’t look at Bruce Lee as the myth, the hero, or the legend. The documentary focuses on the human side of Bruce Lee, who feared moving back to the United States and with Hollywood initially discriminated against the legendary actor as unsellable or only perceived as a sidekick.

The film chronicles Lee’s earliest days, as the son of a Chinese opera star born while his father was on tour in San Francisco, and then raised in Hong Kong over what became at times troubled childhood. Sent to live in America at the age of 18, he began teaching Kung Fu in Seattle and established a following that included his future wife, Linda. His ambition ever-rising, Lee eventually made his way to Los Angeles, where he strove to break into American film and television. There, despite some success as a fight choreographer and actor, it was clear Hollywood wasn’t ready for an Asian leading man—and so he returned to Hong Kong to make the films that make him a legend, his international star skyrocketing just as his life was cut short.

Be Water is told entirely by the family friends and collaborators who knew Bruce Lee best. The film included an extraordinary trove of archive film providing an evocative, immersive visual tapestry that captures Lee’s charisma, his passion, his philosophy, eternal beauty, and the wonder of his art.

The film airs Sunday, June 7, on ESPN and ESPN2 at 9 p.m. EST. It is also available for ESPN+ members anytime after the air date.

LRM Online exclusively spoke with director Bao Nguyen over the phone about the tone and direction of Be Water and telling a different story on Bruce Lee.

Read the full interview below.

Gig Patta: Hi, Bao. How’s it going with you? I’m doing well.

Bao Nguyen: Yeah, things are okay. I’m in Los Angeles right now on the border of all the protests happening this week. I’m doing well.

Gig Patta: I hope you’re safe from both the protests and the coronavirus.

Bao Nguyen: I am. Where are you calling from?

Gig Patta: I’m calling from Fresno. I haven’t been to Los Angeles for quite a while. I used to drive down there three times a week to conduct interviews.

Bao Nguyen: Got it.

Gig Patta: I’ve checked out your film. It’s fascinating. What brought you onto a project for Be Like Water?

Bao Nguyen: It’s Be Water. There’s no “Like” in the middle.

Gig Patta: I’m sorry.

Bao Nguyen: It’s confusing. No worries. There’s a lot of variations of that quote.

I remembered growing up and not seeing a lot of people who looked like me on screen as an Asian-American. When they were on screen, it was easily in a negative portrayal either as sidekick/servant or often the villain. When I was eight or nine-years-old, I remembered watching television Saturday evening and Entered the Dragon was on. I was blown away by someone who looked like me as an Asian-American male and the leading man as the hero in the film. That memory resonated with me when I thought about Bruce Lee. I’m part of a generation that was born ten years after Enter the Dragon came out.

I never got to see the films when they were in theaters, but Bruce Lee always stuck with me–of the mythology and the legacy. As a filmmaker later on in my life, the stories I wanted to tell stories about subject matters that were familiar, but looking at them in a different lens. Bruce Lee was someone who knew the name and the symbol but didn’t know anything about his life. I wanted to explore him more as a human being rather than as a mythical figure. That’s how the concept of the film came about.

Gig Patta: I’m amazed you have such a great memory. We’re part of the same generation, and I barely remembered the Bruce Lee movies.

Bao Nguyen: I remembered that one moment. It was so different from what I had seen on screen. If you asked me the plot to Enter the Dragon, all I would remember is that Bruce Lee was beating up everyone. [Laughs]

Gig Patta: Where did you start if you wanted to do a documentary on Bruce Lee?

Bao Nguyen: Knowing the angle, it’s unpacking the myth of who Bruce Lee was instead by looking at him in an impactful present-day way. I had to start talking to his family—these people who knew him the best, including his students and his friends.

We started researching who was still alive, who had an interesting perspective, or who would explain the story narrative of Bruce Lee that I wanted to explore more–not just only as of the man. We looked at how Hollywood rejected him and what led up to that rejection. There were observations of the story of America viewing Asian-American as docile, subservient figures onscreen.

Knowing that angle, I approached certain interviewed subjects and individuals with that perspective. Although they’ve been speaking about Bruce Lee for most of their lives over 40 plus years, they found the angle refreshing. They were open to talking to me.

We did a bit of traveling. I would retrace Bruce’s steps, right? Such as where he lived in Hong Kong. We went to Hong Kong, Seattle, Oakland, and Los Angeles. From there, I stepped into the shoes of Bruce Lee in a way,

Gig Patta: To get the interview subjects, it sounded like it was reasonably straightforward. They’re very familiar with doing these types of projects.

Bao Nguyen: Actually, it was very hard. They’ve been talking about Bruce Lee for so long, and they’re wondering why I’m telling Bruce Lee’s story again. That’s why I had to come with them with that specific approach of seeing the Bruce Lee story through the lens of being an immigrant American, being an Asian-American.

So many past narratives of Bruce Lee looked at him as this martial arts icon and film icon. They represented him as a deity figure, but not observing Bruce Lee through all the struggles, all the prejudice or discrimination as an Asian-American.

The challenge was convincing them in the first place to do the interview, but also the finding people. Many people are in their late seventies or eighties, and some don’t even have e-mail or cell phones. We were calling landlines and knocking on doors for some people. There was that logistical difficulty.

Gig Patta: Aren’t you concerned that there are already so many documentaries out there on Bruce Lee?

Bao Nguyen: That’s always a concern for any film. For me, I hadn’t seen this perspective on Bruce Lee. It’s the story of Asian-Americans specifically, and not just about Bruce Lee. It’s about America. It’s about the racial history of America and how racial history reflects onto the onscreen representations, especially people of color. We will see how it perpetuates. It turns into this vicious cycle of how we treat other people because of what we view them as though their onscreen representations and definitions.

I wanted to interweave those two narratives. Be Water is the coming of age of Bruce Lee and this coming of history of America. It’s how someone with the charisma and onscreen presence of Bruce Lee rejected by Hollywood. When you watch him on screen, it’s just he’s magnetic. He only has so much star power, but America, for some reason, wasn’t ready for a leading Asian man. I wanted to unravel and explore those ideas more by taking a deeper kind of social context and historical context and to preach these stories.

Gig Patta: I do like the racial observations explored in the documentary. Could you talk about the timing of how things that happened decades ago is still occurring today?

Bao Nguyen: That’s one of the reasons the film is different from many other Bruce Lee documentaries. We always try to make a timeless film, because you don’t know when your movie is going to be watched, be accessible or released. I couldn’t have predicted the things that were going to go on today.

In America, especially with Covid-19, the racial injustice towards George Floyd in Minnesota, and with all the protests, the story became even more relevant. Bruce Lee, as a person of color, was always judged by what he looked like and where he came from instead of deciding a person for all his talents and skills.

In the world of Covid, there are many incidents of anti-Asian racism where people will say, “Go back to China. Go back home.” I’ve been a victim of this too. I’m not even Chinese. Some of my friends’ families lived eight to nine generations in America and told to go back home.

There is this idea of how people judged us based on our faces and discriminated against that immediately. Bruce Lee was the antithesis of that idea. He was meeting people for who they were. It is a very relevant conversation.

With the conversation about racial injustice and police brutality, Bruce Lee’s first student in America was Jesse Glover, who was a victim of police brutality. That’s why he decided to learn martial arts. He was a close friend of Bruce Lee. With those experiences and interactions, it shaped Bruce Lee throughout the rest of his time in America. His philosophy towards everything is with fluidity in the way he taught all different races and all different nationalities.

His relationship with Kareem Abdul Jabbar, he taught him about the civil rights movement, particularly black liberation. In America, there’s always room to learn from each other to be allies when we see racial injustice or injustice of any kind. Hopefully, the audience takes that away, as well as learning more about Bruce as a human being

Gig Patta: Being Asian in this business, Bruce Lee had his particular challenges in Hollywood. Are you experiencing the same difficulties that decades later, personally? Or do you find that things are much different today?

Bao Nguyen: Things are better, right? There are a lot more opportunities, but the problem is still occurring since this question is still being asked. Right? When the question that’s being asked, that’s when we’ve reached this point where it’s no longer a problem.

Another reason I made the film is since the conversation about representation, and inclusion is relevant today. In some ways, it’s trendy. But, when you think about 1960s America and Bruce Lee, how did he achieve that given the racism that many Asian-Americans were facing at that time? The Vietnam War was starting to blow, and a decade earlier, it was with the Korean war. Two decades earlier, World War II had the Japanese seen as the enemy. The Asian-American male was very much the face of the enemy. But then, Bruce broke that mold to be the leading hero. That was a story that had to be uncovered a bit more.

Gig Patta: When you gathered the footage for all of this documentary, was it easy to gather since a lot of it was public domain?

Bao Nguyen: It was pretty difficult because have you seen the film–it’s entirely archival of the film. As many Bruce Lee fans will attest to, there has been a lot of Bruce Lee footage already seen on the Internet. This film is not meant to be definitive on stuff that you’ve never seen before. There’s rare footage in the film, but people have been looking at Bruce Lee footage for 40 years.

The archival we did get was mostly from the family, who had a lot of archival. There was also going to these cities in talking to all these people who knew Bruce. A lot of these photos were personal photos from loved ones like Amy Sanbo. One interesting factoid about the film is that Amy Sanbo was Bruce Lee’s first girlfriend in America. She’s a Japanese American. There’s a photo going around on the Internet supposedly of her and Bruce. I showed her the photo, and she was like, “That’s not me.” There’s this perpetuation that’s her. In this film, we finally get to see her face.

Unfortunately, since they broke up, there are no photos of them together. Amy asked me, “Do you keep photos of your ex?” I answered, “No, I don’t.” [Laughs] This is the first time that people see Amy Sanbo for who she looks like instead of what people think with the photo of her that’s circulating.

There are these little gems in the film. For me, it was the stories are archival that I found the most enriching. I enjoyed talking to Robert [Lee], Bruce’s brother, and Amy, who has never been interviewed outside of a print magazine a couple of decades ago. I was more focused on getting the stories that were important to the pieces of the film.

And then all the other archival was something that we were lucky to get through the family, friends of family, the students and friends. Despite a lot of the archival that we used, we ended up shooting on our own. There’s a lot of impressionistic archival as we wanted to kind of place ourselves in the time of the 1960s as much as possible. It’s part of the cinematic language of the film to shoot everything in this vintage super-8 style.

Gig Patta: I do love the beautiful approach that you used for this documentary, in particularly the credits where you have shown everyone with their personal photos with Bruce, Bruce Lee. That was very touching.

Bao Nguyen: Thank you. That was something that was my intention. It’s from the very beginning because I wanted to talk to people who knew Bruce Lee. A lot of documentaries, for the most part, they looked at the legacy with people who were fans of Bruce Lee or looked up to Bruce Lee. For the most part, 90% of the people that we talked to knew Bruce Lee personally. They were devastated by his early death. They knew his fears, his insecurities, and vulnerabilities.

That is a different part of a Bruce that we don’t get to see in other films. Bruce is this model of masculinity and confidence. Still, there are moments in the film where Robert talked about Bruce being anxious about going to America and crying before he left. Bruce was scared of growing old and being coming to a frail man. These are insights never really heard in the past narratives about Bruce.

Gig Patta: Let me wrap it up with a one, one last question with you. Why is ESPN the perfect outlet for Be Water?

Bao Nguyen: For me, 30 for 30, as a film series, is one of the best set of documentaries on that ever made. By watching O.J.: Made in America, they used O.J. Simpson’s story as a vessel to talk about race in America and the black experience. I wanted to talk about with Be Water. Not just about Bruce Lee, but using Bruce Lee as a vessel for talking about the Asian American experience.

ESPN is a big, wide platform to be able to discuss these issues. He was not necessarily the most visible sports figure. We used sports as a way to get into a deeper problem and a more in-depth narrative into more layers of who Bruce Lee was and who America is in a way.

Gig Patta: Excellent answer. Thank you very much for speaking with me. I certainly hope a lot of people check out Be Water.

Bao Nguyen: Great. Thank you so much.

The film airs Sunday, June 7, on ESPN and ESPN2 at 9 p.m. EST. It is also available for ESPN+ members anytime after the air date.

ALSO READ: Rodrigo Massa Interview: Brazilian Netflix Heartthrob Talks About New Album La Fiesta

Source: LRM Online Exclusive, ESPN

FOR FANBOYS, BY FANBOYS

Have you checked out LRM Online’s official podcasts and videos on The Genreverse Podcast Network? Available on YouTube and all your favorite podcast apps, This multimedia empire includes The Daily CoG, Breaking Geek Radio: The Podcast, GeekScholars Movie News, Anime-Versal Review Podcast, and our Star Wars dedicated podcast The Cantina. Check it out by listening on all your favorite podcast apps, or watching on YouTube!

Subscribe on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | SoundCloud | Stitcher | Google Play

FOR FANBOYS, BY FANBOYS

Have you checked out LRM Online’s official podcasts and videos on The Genreverse Podcast Network? Available on YouTube and all your favorite podcast apps, This multimedia empire includes The Daily CoG, Breaking Geek Radio: The Podcast, GeekScholars Movie News, Anime-Versal Review Podcast, and our Star Wars dedicated podcast The Cantina. Check it out by listening on all your favorite podcast apps, or watching on YouTube!

Subscribe on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | SoundCloud | Stitcher | Google Play